|

Big Joy

The Adventures of James Broughton

Frisky Divinity Productions,

2013

Directors:

Stephen Silha,

Eric Slade,

Co-director/editor:

Dawn Logsdon

Starring;

James Broughton

(archival),

Neeli Cherkovski,

Lawrence Ferlinghetti,

Jack Foley,

Alex Gildzen,

Anna Halprin,

Suzanna Hart,

Davey Havok,

George Kuchar

Armistead Maupin

Joel Singer,

Pauline Kael

(archival)

Unrated,

82 minutes |

To The Beat Of A Different Drummer

by

Michael D. Klemm

Posted online July, 2014

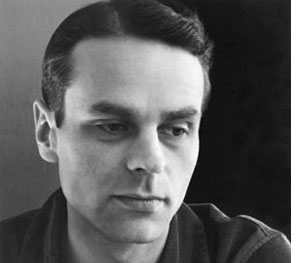

James Broughton (1913-1999) is one of the most interesting underground queer artists you probably have never heard of. (His name was unfamiliar to me too until a few weeks ago.) He is the subject of a new documentary, Big Joy: The Adventures of James Broughton (2013). Broughton was a poet and a filmmaker who taught his audiences to “follow [their] own weird.” His films transcend gender and sex roles and the copious nudity in his 1968 film, The Bed, was a hit with the era’s counterculture. One of Big Joy’s narrators calls him “an outsider’s outsider, under the underground.” Writer Armistead Maupin (Tales Of The City) tells us that “he had a way of getting at the serious by focusing on the silly.” |

Big Joy is directed by Stephen Silha, who knew Broughton for the last ten years of his life, and Eric Slade, who directed Hope Along The Wind: The Life Of Harry Hay in 2002. Dawn Logsdon is also listed as co-director and editor. Using clips from Broughton’s films, archival footage, diary excerpts, and interviews with several of the man’s contemporaries (along with a few modern poets) the filmmakers deliver a portrait of the artist that is both entertaining and educational. Their approach to the subject is often playful, not unlike the artist himself. Big Joy is directed by Stephen Silha, who knew Broughton for the last ten years of his life, and Eric Slade, who directed Hope Along The Wind: The Life Of Harry Hay in 2002. Dawn Logsdon is also listed as co-director and editor. Using clips from Broughton’s films, archival footage, diary excerpts, and interviews with several of the man’s contemporaries (along with a few modern poets) the filmmakers deliver a portrait of the artist that is both entertaining and educational. Their approach to the subject is often playful, not unlike the artist himself.

|

|

Over the years, I’ve discovered much unexpected overlap between our history and other art movements. The Beat Generation grew out of the San Francisco Renaissance of the mid 1940s and Broughton was one of the leading figures of that movement. Shifting his focus from poetry to filmmaking, he made The Potted Psalm in 1946 and it was the first Bay Area avant-garde film. Over the years, I’ve discovered much unexpected overlap between our history and other art movements. The Beat Generation grew out of the San Francisco Renaissance of the mid 1940s and Broughton was one of the leading figures of that movement. Shifting his focus from poetry to filmmaking, he made The Potted Psalm in 1946 and it was the first Bay Area avant-garde film.

|

Broughton claims to have been visited by a fairy named Hermy, when he was 3 years old, who told him to become a poet. (Be prepared to roll your eyes now and then during this film.) He was born to a prosperous banking family and his toxic relationship with his mother lasted well into his adulthood. During the 1930s, Broughton had several male partners, including Harry Hay, who later founded the Mattachine Society and the Radical Faeries. For a time, during the 1940s, he lived with future film critic Pauline Kael. She encouraged his filmmaking endeavors but their relationship ended after she got pregnant. Broughton moved on to his next important partner, Kermit Sheet, the director of a theatre called the Playhouse, and they made a handful of short, sensual films together. While essentially straight, their cinema featured many fast and fleeting homoerotic images. Broughton claims to have been visited by a fairy named Hermy, when he was 3 years old, who told him to become a poet. (Be prepared to roll your eyes now and then during this film.) He was born to a prosperous banking family and his toxic relationship with his mother lasted well into his adulthood. During the 1930s, Broughton had several male partners, including Harry Hay, who later founded the Mattachine Society and the Radical Faeries. For a time, during the 1940s, he lived with future film critic Pauline Kael. She encouraged his filmmaking endeavors but their relationship ended after she got pregnant. Broughton moved on to his next important partner, Kermit Sheet, the director of a theatre called the Playhouse, and they made a handful of short, sensual films together. While essentially straight, their cinema featured many fast and fleeting homoerotic images.

|

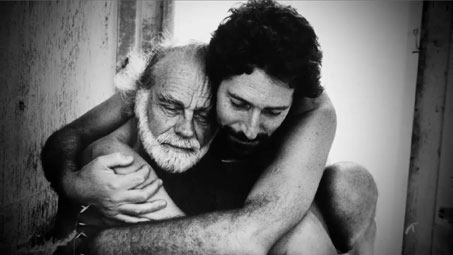

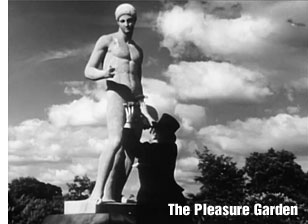

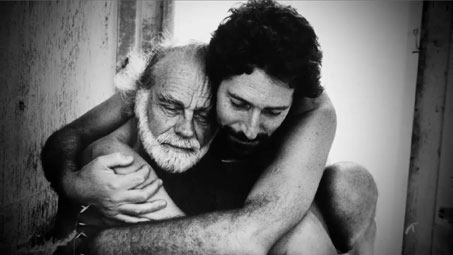

The political climate for artists was not good in the U.S. because of McCarthyism and so, in 1951, James and Kermit sailed to Europe for an extended stay. Their short film, The Pleasure Garden (1954), was presented with a special award at Cannes by Broughton’s idol, avante-garde filmmaker Jean Cocteau (1930’s Le Sang d’un Poète). Cocteau congratulated him for being “an American who made a French film in England.” Turning down a commercial film, he returned to San Francisco to follow his muse and be a poet again just as the Beat Generation poets were taking the town by storm. Following years of Jungian therapy, Broughton married costume designer Suzanna Hart in 1962. They had two children together and he started making films again. And then at the age of 61, while teaching college film classes in 1975, he fell in love with one of his students, Joel Singer. Believing he had finally found the soulmate that eluded him all his life, he divorced his wife and spent the rest of his days with Joel in his most artistic, and nourishing, relationship. The political climate for artists was not good in the U.S. because of McCarthyism and so, in 1951, James and Kermit sailed to Europe for an extended stay. Their short film, The Pleasure Garden (1954), was presented with a special award at Cannes by Broughton’s idol, avante-garde filmmaker Jean Cocteau (1930’s Le Sang d’un Poète). Cocteau congratulated him for being “an American who made a French film in England.” Turning down a commercial film, he returned to San Francisco to follow his muse and be a poet again just as the Beat Generation poets were taking the town by storm. Following years of Jungian therapy, Broughton married costume designer Suzanna Hart in 1962. They had two children together and he started making films again. And then at the age of 61, while teaching college film classes in 1975, he fell in love with one of his students, Joel Singer. Believing he had finally found the soulmate that eluded him all his life, he divorced his wife and spent the rest of his days with Joel in his most artistic, and nourishing, relationship.

|

|

Talking heads put the events of his life into historical perspective, and newsreel footage of gay men being arrested establish the fear of being queer in the 1950s. Like many gay men of his era, Broughton drifted in and out of relationships with women to conform to society; his queer self winning in the end after abundant attempts at suppression. He found expression in his poems and his cinema. The voice of the artist often dominates the soundtrack through interview snippets and poetry readings. The charming clips from his films are among the documentary's highlights. These early shorts recall Cocteau’s surrealist cinema while also anticipating the later underground films of Kenneth Anger. The sublimely silly film clips, many featuring shirtless men, are balanced by sobering commentary about the artist’s recurring thoughts of suicide. Grim selections from his poems are read aloud to grungy, animated text. |

The film is short (82 minutes) and doesn’t overstay its welcome. The pace is usually brisk with a lot of frantic cutting, and cameras panning over and zooming into old photos. Like any documentary, the attention paid to the little details make watching it worthwhile. Laurence Ferlinghetti, (owner of the famous City Lights bookstore, and publisher of Alan Ginsberg’s Howl), recounts introducing Broughton to the Beats. Pauline Kael and Kermit Sheet discuss their relationships with Broughton in audio tape excerpts. I admit that, aside from Ferlinghetti and Maupin, the talking heads were mostly unknown to me - a few more recognizable names might have added more interest. Several modern poets read selections from Broughton’s verses – but there’s a bit too much of it during the film’s third act. Poetry readings aren’t everyone’s cup of tea and the film meandered for me in the last stretch. The film is short (82 minutes) and doesn’t overstay its welcome. The pace is usually brisk with a lot of frantic cutting, and cameras panning over and zooming into old photos. Like any documentary, the attention paid to the little details make watching it worthwhile. Laurence Ferlinghetti, (owner of the famous City Lights bookstore, and publisher of Alan Ginsberg’s Howl), recounts introducing Broughton to the Beats. Pauline Kael and Kermit Sheet discuss their relationships with Broughton in audio tape excerpts. I admit that, aside from Ferlinghetti and Maupin, the talking heads were mostly unknown to me - a few more recognizable names might have added more interest. Several modern poets read selections from Broughton’s verses – but there’s a bit too much of it during the film’s third act. Poetry readings aren’t everyone’s cup of tea and the film meandered for me in the last stretch.

|

A good documentary should tell all the sides of the story and Big Joy isn’t just a love letter to Broughton. Yes, the filmmakers like to present him as an iconoclast who marched to the beat of a different drummer. The emphasis is on joy and unbridled hedonism, and much of the footage of the artist enjoying his twilight years with Singer is indeed idyllic and beautiful. But interviews with Singer, waxing poetic about his years with the artist, are balanced by reminiscences from Broughton’s ex-wife and his abandoned son. Rather than only celebrating silliness, I found it admirable that the directors didn’t gloss over the pain he caused his wife and children. After all, when you think about it, he spent all of his life unable to decide if he was gay or straight; leaving a lot of broken hearts in his wake. A good documentary should tell all the sides of the story and Big Joy isn’t just a love letter to Broughton. Yes, the filmmakers like to present him as an iconoclast who marched to the beat of a different drummer. The emphasis is on joy and unbridled hedonism, and much of the footage of the artist enjoying his twilight years with Singer is indeed idyllic and beautiful. But interviews with Singer, waxing poetic about his years with the artist, are balanced by reminiscences from Broughton’s ex-wife and his abandoned son. Rather than only celebrating silliness, I found it admirable that the directors didn’t gloss over the pain he caused his wife and children. After all, when you think about it, he spent all of his life unable to decide if he was gay or straight; leaving a lot of broken hearts in his wake.

|

We learn from Kael that he flirted with everyone he met. “He rode off into the sunset with some guy,” his wife, Suzanna Hart tells us. “That was very sad for me, but not for him, which was…very irritating.” In her segments, Hart keeps her emotions in check but you can clearly read the sadness and anger in her face. The son doesn’t have much good to say about his absent father and the two daughters (the first by Kael and the second by Hart) both refused to be interviewed for the film. Singer has a lot to say about their blissful decades together, but he also comes off a bit heartless when he shows no guilt over breaking up what he calls Broughton’s “loveless” marriage. We learn from Kael that he flirted with everyone he met. “He rode off into the sunset with some guy,” his wife, Suzanna Hart tells us. “That was very sad for me, but not for him, which was…very irritating.” In her segments, Hart keeps her emotions in check but you can clearly read the sadness and anger in her face. The son doesn’t have much good to say about his absent father and the two daughters (the first by Kael and the second by Hart) both refused to be interviewed for the film. Singer has a lot to say about their blissful decades together, but he also comes off a bit heartless when he shows no guilt over breaking up what he calls Broughton’s “loveless” marriage.

|

Pauline Kael thought that Broughton made the biggest mistake of his life when he turned down a studio film after winning the prize at Cannes. One can only speculate what paths his life might have taken if he hadn't decided to stay true to his art. Broughton surely never regretted his decision and, for good or bad, lived his life the way he wanted. I admit that some of the love guru stuff gets tiresome after awhile, but the joy that can still be seen in his face as a very old man cannot help but inspire. I think the filmmakers inflate his significance a bit, but Broughton is a fascinating figure and Big Joy is a good introduction to his life and his work. Pauline Kael thought that Broughton made the biggest mistake of his life when he turned down a studio film after winning the prize at Cannes. One can only speculate what paths his life might have taken if he hadn't decided to stay true to his art. Broughton surely never regretted his decision and, for good or bad, lived his life the way he wanted. I admit that some of the love guru stuff gets tiresome after awhile, but the joy that can still be seen in his face as a very old man cannot help but inspire. I think the filmmakers inflate his significance a bit, but Broughton is a fascinating figure and Big Joy is a good introduction to his life and his work.

|